We’ve learned a lot in our journey towards Pesach. These are lessons to bring with us into Yom Tov.

We’ve dragged our weary bodies into Pesach, hopefully a little more refreshed than usual thanks to a solid Shabbos nap. Now what? We have a week of celebrating, of feasting, of rejuvenation, and a week of incredible potential for connection to Hashem.

As with every season in the Jewish calendar, there is so much depth and meaning to the yom tov, so much that we can reflect upon and take with us into life after yom tov.

From the many beautiful values that Pesach represents, I’ve chosen just eight, one for each day of the chag.

The Essence of Faith

Pesach is the season of hope and deliverance. We celebrate the geulah of the past and look toward the future, the ultimate geulah shleimah. It is a time when anything is possible, if we believe strongly enough and we daven hard enough.

It seems impossible—we’ve been in galus for so many years and we know no other reality, can’t fathom a future other than the one we can envision with the frame of reference that we have.

And we seem to be so far gone in ruchniyus, we have strayed so far from the Source, that we wonder how it is possible to ever find our way back home.

And yet, our people in Mitzrayim were no different. They were born into slavery; they didn’t know a reality other than servitude and torture. They were so deeply immersed in tumah, one more level down and they’d have been gone forever. And then, when Hashem decided the time was ripe, when our cries rang strongly enough, nothing in the world could stop the geulah from happening. After so many years with the light at the end of the tunnel nowhere near visible, we hurtled out of that land so fast, our dough didn’t even have time to rise. That is why matzah is the centerpiece of this yom tov, whose preparation centers around getting so thoroughly rid of anything that is not matzah. As we work on our emunah, the avodah of this chag, we work on believing with all of our heart that should He will it, we will be redeemed so quickly that we won’t know what happened to us.

This goes for the communal geulah as well as each Yid and his personal tzarah. There is no such thing as a Yid with no hope. And we may be entrenched in a reality so dark and so deep, there seems to be no way we can ever dig our way out of it, no way we can ever find the light. But He is there, and He will make it happen when the time is right. And He might just make it happen so fast that we will embrace our long-awaited salvation with the dough still raw on our backs.

Keep hoping, keep praying, keep believing.

The Caring of Strangers

From when we’re very young, we learn why we dip our pinky into the wine and remove some of it when we articulate the makkos. My kindergarten daughter can tell you that even though the Mitzriyim hurt us, they are still creations of Hashem and we still need to care when they are hurt.

Our joy is diminished when another suffers, no matter who he is or where he comes from.

It’s a powerful lesson in empathy that we reinforce again when we don’t say a complete Hallel for most of Pesach, decreasing some of our exultation in recognition of those who perished in the Yam Suf, wicked as they may have been.

It’s a powerful reminder that every single person is a creation of Hashem and must be treated with empathy and respect. We can maintain a kinship and brotherhood with our own; we can feel proud to be the am hanivchar, but that doesn’t go along with disparaging and disrespecting eino Yehudim. If anything, being the chosen children of Hashem comes along with the mandate to exhibit empathy, compassion and respect for every human being.

If we can remove some wine for those who beat us to death, we can surely pour some for the average Joe on the street.

The Acceptance of Brothers

For strangers, at the very most acquaintances, “pouring some wine” may be adequate. When it’s brothers we are talking about, Pesach teaches us to open our arms wide. We start the seder by first welcoming anyone who is hungry or in need to join us in our home.

It is our prerequisite to enjoying Hashem’s bounty. First we must share it with others. We don’t do background checks, we don’t discriminate based on yichus, frumkeit or anything else. Kol dichfin yeisei v’yeichal.

We have a special section in our haggadah geared toward different types of Yidden. We may have sharper answers for some, we may disapprove of their attitudes, but the haggadah teaches us that each and every one of Hashem’s children, from the chacham to the rasha and everyone in between, is welcome at our table.

Kol dichfin, arba banim—when it comes to His chosen children, there is room for everyone at our table. (Eliyahu Hanavi?)

We don’t say, “Anyone who is wearing the right garb,” or, “Anyone who boasts the right accent.” We say anyone who is hungry, anyone who wants to be here, who wants to partake and be a part of this.

The Power of Mesorah

The seder is set up in a way that ensures the mesorah stays alive. Son asks father, father answers son, who eventually goes on to answer his own son. Transmitting our legacy to our children is what keeps Klal Yisroel alive and thriving. Last year we all (or most of us at least!) spent the seder in quarantine, with only those who share our walls for company. For so many, it was our first seder like this, and for so many it was an unexpectedly beautiful Pesach. But as much as we made the most of it and connected to Hashem poignantly through a very dark time, there was definitely a lack. We missed that mesorah. We missed grandparents and grandchildren sitting at the same table, continuing a legacy that has been transmitted for generations, going back to the original Yetzias Mitzrayim.

This year, hopefully many of us will rejoin our generations, and we can appreciate that like never before. Drink in the traditions, the legacies, and strengthen the chains that connect past, present, and future. Revel in the questions and respect the answers, because that is what makes a nation endure forever.

The Meaning of Freedom

Z’man cheiruseinu. Freedom means different things to different people. Some people think freedom means being able to do what we want whenever we want to. But the Jewish definition of freedom is the ability to create a meaningful life with authentic values and to create a close connection with our Creator. Freedom is living a life of constant growth and striving to live up to our potential.

We were taken out of Mitzrayim not to dance into the sunset to the tune of our own choosing, but to become servants immediately after our release. Only forty days later we were standing at the foot of the mountain, binding ourselves to Hashem through a list of rules and regulations that seem endless to the uninitiated.

What kind of freedom is that?

The only kind.

Serving Hashem gives our neshamah the freedom to soar, unburdened by the shackles of Olam Hazeh.

The Danger of Ego

The lengths to which we go to get rid of every last vestige of chametz from our home is a source of puzzlement to outsiders, and even sometimes to ourselves. Armed with toothpicks and Ajax, Mr. Clean and Mrs. Determination, we wage war against the leavened enemy. At the same time, we take pains to get rid of the se’or sheb’isah whose crumbs have lodged in every corner of our hearts. The se’or sheb’isah literally means the leaven in the dough, but it is a euphemism for the yetzer hara himself.

And why is the yetzer hara referred to as the leaven in the dough? The leaven is the yeast, the substance added to bread to make it puff up. It’s the ego. Our evil inclination is rooted in our ego, the sense of entitlement, of “I” and only “I,” that stands between us and Hashem. When our ego gets involved in our decision making, it is our yetzer hara, our chametz. When I bake challah with my little girls, our favorite part is punching out the air bubbles before kneading the dough. We each (after scrubbing well of course) take one fist and enthusiastically punch down the dough while chanting, “Yetzer hara, go away!” It’s the yetzer hara that puffs us up, that causes us to act out of pride and not humility, out of a sense of desire rather than servitude to Hashem.

And so, as we clean the chametz out of every corner, let us remove the ego that holds us back from doing the right thing and instead embrace the matzah, the humility that comes with a true sense of self-worth and desire to do Hashem’s will with love and devotion.

The Journey of the Afikoman

It’s a simple matzah, but it has quite the journey. It starts off like all the other matzahs, waiting in anticipation under the velvet matzah cover. Sandwiched between its brothers, it is part of something great, the glorious nation whose birth we celebrate on this night.

Then, it is taken out and broken in half. It goes missing—later found to have been stolen—and is the subject of frantic searching and heated negotiations. Finally, finally, it is found. Sometimes it is lucky enough to remain just a half a matzah, while in other homes the turbulence and not such gentle hands has caused it to become further broken into millions of tiny pieces. Either way, it is then consumed in great joy, the grand finale of a beautiful and uplifting seder, serenaded with songs of praise of Hashem and yearning for the ultimate geulah.

It is the story of our People, broken to pieces, cast aside, lost, wandering from land to land, before ultimately coming back home again, bringing our entire journey, our entire seder, full circle.

All through the seder, the afikoman is seen as a symbol of hope as half-lidded young eyes force themselves open for just a moment longer in anticipation of what is yet to come.

It is our future, the gifts that await us after a tumultuous journey. It is the story of Pesach itself, of beatings and brokenness, of wandering and despair, and then of the great revelation, the redemption itself.

And it is a reminder that though we may feel broken today, lost and confused, there are great things awaiting us. There is a dessert. There is an afikoman that is so sweet and so enduring, that nothing else can possibly follow it. So special that “Ein maftirin achar haPesach afikoman.”

And sometimes, we will even find that when we get to the afikoman, it is that much sweeter because of all we have endured to reach it.

Let us embrace the journey with all of its shards and all of its wandering, even as we anticipate the beautiful destination.

The Joy of Renewal

It’s no coincidence that Pesach is in the spring. As we know, it’s an integral aspect of the yom tov. So integral, that we add an extra month to our calendar to ensure the seasons align. So integral that it is the very name of the yom tov. Chag HaAviv.

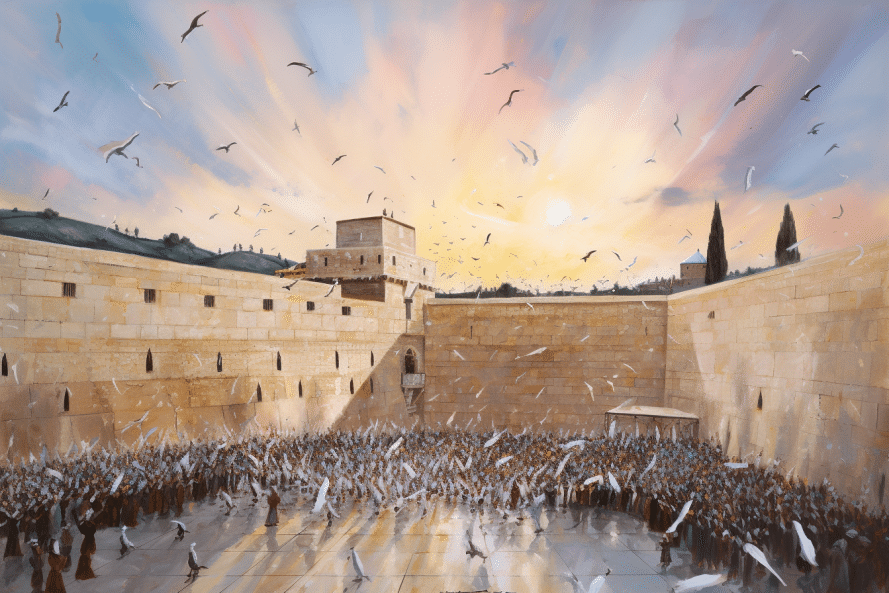

The signs of spring are hard to miss, as we start awakening to the sound of chirping birds again, their migration back home coinciding with the migration of our bachurim home for Pesach bein hazmanim. We look around as our perennials spring to life again and our sickly yellow grass transforms to a lush green lawn. Our gardens become awash in color and the spring returns to our steps as well. There is a certain hope and promise in spring, as ground long fallow springs to life, flowers long dormant become vibrant again.

It’s not only the weather outside experiencing a rebirth. The essence of Pesach contains in it the birth of our nation. The events of Pesach set the stage for our redemption from the depths of slavery to the heights of kedushah and malchus. In one night, we went from downtrodden, oppressed slaves to magnificent, holy royalty.

On the night of Pesach, Klal Yisroel was born as a nation in the service of Hashem.

And each of us, if we tap into the koach of Pesach, can experience our own renewal, rebirth and rejuvenation.

Reprinted with permission from the Lakewood Shopper Family Room.

Beautiful!